A tragedy

A tragedy could have been averted, but no one was willing to touch the hot issue of curbing the mass pilgrimage of a quarter of a million religious men, women, and children for one night of celebration at the grave of Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai,

“the Rashbi,” a Mishnaic sage and leading disciple of Rabbi Akiva in the 2nd century. The day of celebration is Lag BaOmer, the 33rd day of

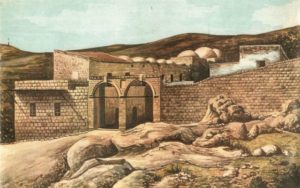

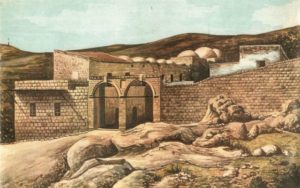

counting of the Omer, and the day on which he revealed the deepest secrets of kabbalah in the form of the Zohar (Book of Splendor, literally ‘radiance’), a landmark text of Jewish mysticism. According to kabbalistic tradition, this day marks the hillula (celebration, interpreted by some as anniversary of the death) of the Rashbi. This association has spawned several well-known customs and practices on Lag BaOmer, including the lighting of bonfires, pilgrimages to the tomb of Bar Yochai in the northern Israeli town of Meron, and various customs at the tomb itself.

It so happened that I had to travel to the center of the country for an early-afternoon meeting on the 29

th of April 2021. I decided to take the train, since it was more convenient and economical than driving and getting stuck in traffic jams. The traffic of any day is chaotic, but Thursday afternoon is especially heavy. I boarded the train in my hometown, Karmiel, which is the final station for northbound trains. Had I paid attention, I would have realized that it is also the closest station to Meron, the place of Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai’s grave. The trip south before noon was very pleasant. The train provides assistance to people with disabilities, and being with a walker, I received royal treatment and assistance in boarding and when I had to change trains.

My trip back was scheduled for 5 PM on the fast, direct train. I found this Haiku:

“Wherever you go, there you are. Your luggage is another story”

which fits what happened. When I got off the train that connected to it, the helper unfortunately mistook a piece of luggage that was sitting nearby as mine, and placed it on the platform. Since it was not mine, someone will arrive perhaps at the airport without his luggage. If not for the assistance of the train workers, I would not have been able to board the train, let alone find a seat. Two young girls were asked by the assistant to get up from the seats reserved for the disabled, and I was seated. An elderly lady sat beside me and told me she was vaccinated, so I need not worry. Across from me sat a young man who was helping the sight-impaired woman sitting beside him to calm the large companion dog on her lap. The PA system kept telling the passengers that according to health regulations masks must be worn at all times, that no eating or drinking is allowed on the train, and that everyone must keep their distance. Well, that was a good joke. People were packed like sardines, leaning on each other, filling nonexistent spaces and competing for a foothold with baby carriages and young children clambering over each other. Most of this mass of people were ultraorthodox Jews heading to Karmiel, where the Transit Authority provided shuttle buses to Meron, so when the woman with the dog had to get off, she was lucky to be assisted by the train workers. The two young girls were now able to sit across from me. They were distressed, and visibly frightened. They were coming home from a boarding school to Karmiel for the weekend, and I told them I would give them a ride home. When we arrived in Karmiel, there was no way we could have made it out of the station without assistance. A brave worker used his whistle to clear a path for us, and continued doing so until we cleared the station. When I arrived home, I told my husband I just arrived with “the train from hell”. Or more accurately “the train to hell.” When I saw the pictures of some of the 45 dead, among them children, I recognized some who had been standing and laughing in the aisle next to me. 150 more were injured, some of them critically. The fact that there were no women and small children among the dead or injured is because of the gender segregation. For once, that was a good thing.

Mass pilgrimages to tombs of holy sages, martyrs, or healers, are known in all religions. In some it is proscribed as part of religious practice, and in others it is established by popular movements and mystic beliefs. The pilgrimage on Lag BaOmer to Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai’s grave has another explanation which stems from a Talmudic passage. It states that during the time of Rabbi Akiva, 24,000 of his students died from a divinely-sent plague during the counting of the Omer. The Talmud goes on to say that this was because they did not show proper respect to one another.

According to a tradition of the Talmudic rabbis, the plague ended on Lag Ba Omer. For this reason, the period of mourning which coincides with the counting of the Omer is suspended on Lag BaOmer. According to Jewish religious tradition, after the death of Rabbi Akiva’s 24,000 students, he was left with only five students, among them Rabbi Shimon Bar Yochai. The latter went on to become the greatest teacher of Torah in his generation, and is purported to have authored the Zohar, a landmark text of Jewish mysticism. The actual authorship of the Zohar has been disputed, and scholarship generally points to Moses de León as the author of the Zohar, pseudo-epigraphically attributed to Bar Yochai by him in an attempt to legitimize the work.

The Zohar calls the day of Bar Yochai’s death a hillula – celebration. Rabbi Chaim Vital, the main disciple of Rabbi Isaac Luria and author of Etz Chaim, was the first to name Lag BaOmer as the date of Bar Yochai’s hillula. According to the Zohar (III, 287b–296b), on the day of Bar Yochai’s death, he revealed the deepest secrets of the Kabbalah. Lag BaOmer therefore became a day of celebration of the great light (i.e., wisdom) that Bar Yochai brought into the world.

Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson, writes in his Likkutei Sichos that a deeper reason for the term Lag BaOmer is that the Hebrew words Lag BaOmer (ל״ג בעמר, spelled without the “vav”), have the same “gematria” – numerical count, as Moshe (משה, Moses). He writes that Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai, whose anniversary of death is traditionally observed on this day, was mystically a spark of the soul of Moses. It is customary at the Meron celebrations, dating from the time of Rabbi Isaac Luria, that three-year-old boys be given their first haircuts (upsherin), while their parents distribute wine and sweets. Similar upsherin celebrations are simultaneously held in Jerusalem at the grave of Shimon Hatzaddik for Jerusalemites who cannot travel to Meron. This explains the multitude of families with little children traveling on the train to Meron.

The best-known custom of Lag BaOmer is the lighting of bonfires throughout Israel and worldwide wherever religious Jews can be found. In Meron, the burial place of Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai and his son, Rabbi Eleazar, hundreds of thousands of Jews gather throughout the night and day to celebrate with bonfires, torches, song and feasting. This was a specific request by Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai of his students. Some say that as Bar Yochai gave spiritual light to the world with the revelation of the Zohar, bonfires are lit to symbolize the impact of his teachings. As his passing left behind such a “light”, many candles and/or bonfires are lit. Another reason for the lighting of bonfires is brought by the book Bnei Issachar. On the day of his death, Rabbi Shimon Bar Yochai said, “Now it is my desire to reveal secrets… The day will not go to its place like any other, for this entire day stands within my domain…” Daylight was miraculously extended until Rabbi Shimon completed his final teaching and died. This symbolized that all light is subservient to spiritual light, and particularly to the primeval light contained within the mystical teachings of the Torah. As such, the custom of lighting fires symbolizes this revelation of powerful light. Historically, children across Israel and abroad used to go out and play with bows and arrows, reflecting the Midrashic statement that the rainbow (the sign of God’s promise to never again destroy the earth with a flood; Genesis 9:11–13) was not seen during Bar Yochai’s lifetime, as his merit protected the world.

In modern Israel, early Zionists redefined Lag BaOmer from a rabbinic-oriented celebration to a commemoration of the Bar Kokhba revolt against the Roman Empire. For Zionists, the bonfires are said to represent the signal fires that the Bar Kokhba rebels lit on the mountaintops to relay messages. The Romans forbade the kindling of fires that were used to signal the start of each Jewish month and thus determine the dates of holidays. This interpretation of the holiday reinforced the Zionist reading of Jewish history and underscored their efforts to establish an independent Jewish state. As

Rabbi Benjamin Lau writes in Haaretz:

This is how Lag BaOmer became a part of the Israeli-Zionist psyche during the first years of Zionism and Israel. A clear distinction became evident between Jews and Israelis in the way the day was celebrated: The religious Jews lit torches in Rashbi’s [Shimon bar Yochai’s] honor and sang songs about him, while young Israelis, sitting around an alternative bonfire, sang about a hero “whom the entire nation loved” and focused on the image of a powerful hero who galloped on a lion in his charges against the Romans.

Lag Ba Omer is also marked in the Israel Defense Forces as a week of the Gadna program (youth brigades) which were established on Lag Ba Omer in 1941and which bear the emblem of a bow and arrow.

Beyond our back yard there is a footpath above the wadi and nature reserve. Every year except last year during the pandemic we witnessed young children gathering planks of wood and any kind of flammable material for creating bonfires. We even gathered with a bunch of neighbors and their children around a lovely bonfire at the abandoned lot beside our houses and baked potatoes wrapped in aluminum foil in the fire.

We sang songs, ate watermelon, and when we finished, we made sure the fire was doused with sand and water so it would not spread. Indeed, one year we found a fire burning on the footpath below our back yard, and called the firefighters. When he saw the embers still smoldering in the morning, my husband took things into his own hands and put out the fire with a pail of water. I’d really rather have these kinds of memories than the horrible sights from the trampling of masses.

I know that for the past 12 years there have been negotiations with the Safed Sefardi Religious Authority to transfer responsibility for the tomb (including securing Lag BaOmer events) to the Israeli legal authorities. In that case, perhaps the number of worshipers will indeed be limited to the safe capacity of the space. I am certainly for freedom of practice and respect of each other, but within the bounds of safety. Last year’s pandemic showed that the government caves in to political pressures, even on questions of life and death. Unfortunately this event clearly demonstrated the results of such conduct.

A tragedy could have been averted, but no one was willing to touch the hot issue of curbing the mass pilgrimage of a quarter of a million religious men, women, and children for one night of celebration at the grave of Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai,

A tragedy could have been averted, but no one was willing to touch the hot issue of curbing the mass pilgrimage of a quarter of a million religious men, women, and children for one night of celebration at the grave of Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai, “the Rashbi,” a Mishnaic sage and leading disciple of Rabbi Akiva in the 2nd century. The day of celebration is Lag BaOmer, the 33rd day of counting of the Omer, and the day on which he revealed the deepest secrets of kabbalah in the form of the Zohar (Book of Splendor, literally ‘radiance’), a landmark text of Jewish mysticism. According to kabbalistic tradition, this day marks the hillula (celebration, interpreted by some as anniversary of the death) of the Rashbi. This association has spawned several well-known customs and practices on Lag BaOmer, including the lighting of bonfires, pilgrimages to the tomb of Bar Yochai in the northern Israeli town of Meron, and various customs at the tomb itself.

“the Rashbi,” a Mishnaic sage and leading disciple of Rabbi Akiva in the 2nd century. The day of celebration is Lag BaOmer, the 33rd day of counting of the Omer, and the day on which he revealed the deepest secrets of kabbalah in the form of the Zohar (Book of Splendor, literally ‘radiance’), a landmark text of Jewish mysticism. According to kabbalistic tradition, this day marks the hillula (celebration, interpreted by some as anniversary of the death) of the Rashbi. This association has spawned several well-known customs and practices on Lag BaOmer, including the lighting of bonfires, pilgrimages to the tomb of Bar Yochai in the northern Israeli town of Meron, and various customs at the tomb itself.  It so happened that I had to travel to the center of the country for an early-afternoon meeting on the 29th of April 2021. I decided to take the train, since it was more convenient and economical than driving and getting stuck in traffic jams. The traffic of any day is chaotic, but Thursday afternoon is especially heavy. I boarded the train in my hometown, Karmiel, which is the final station for northbound trains. Had I paid attention, I would have realized that it is also the closest station to Meron, the place of Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai’s grave. The trip south before noon was very pleasant. The train provides assistance to people with disabilities, and being with a walker, I received royal treatment and assistance in boarding and when I had to change trains.

My trip back was scheduled for 5 PM on the fast, direct train. I found this Haiku:

It so happened that I had to travel to the center of the country for an early-afternoon meeting on the 29th of April 2021. I decided to take the train, since it was more convenient and economical than driving and getting stuck in traffic jams. The traffic of any day is chaotic, but Thursday afternoon is especially heavy. I boarded the train in my hometown, Karmiel, which is the final station for northbound trains. Had I paid attention, I would have realized that it is also the closest station to Meron, the place of Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai’s grave. The trip south before noon was very pleasant. The train provides assistance to people with disabilities, and being with a walker, I received royal treatment and assistance in boarding and when I had to change trains.

My trip back was scheduled for 5 PM on the fast, direct train. I found this Haiku:

Mass pilgrimages to tombs of holy sages, martyrs, or healers, are known in all religions. In some it is proscribed as part of religious practice, and in others it is established by popular movements and mystic beliefs. The pilgrimage on Lag BaOmer to Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai’s grave has another explanation which stems from a Talmudic passage. It states that during the time of Rabbi Akiva, 24,000 of his students died from a divinely-sent plague during the counting of the Omer. The Talmud goes on to say that this was because they did not show proper respect to one another.

According to a tradition of the Talmudic rabbis, the plague ended on Lag Ba Omer. For this reason, the period of mourning which coincides with the counting of the Omer is suspended on Lag BaOmer. According to Jewish religious tradition, after the death of Rabbi Akiva’s 24,000 students, he was left with only five students, among them Rabbi Shimon Bar Yochai. The latter went on to become the greatest teacher of Torah in his generation, and is purported to have authored the Zohar, a landmark text of Jewish mysticism. The actual authorship of the Zohar has been disputed, and scholarship generally points to Moses de León as the author of the Zohar, pseudo-epigraphically attributed to Bar Yochai by him in an attempt to legitimize the work.

The Zohar calls the day of Bar Yochai’s death a hillula – celebration. Rabbi Chaim Vital, the main disciple of Rabbi Isaac Luria and author of Etz Chaim, was the first to name Lag BaOmer as the date of Bar Yochai’s hillula. According to the Zohar (III, 287b–296b), on the day of Bar Yochai’s death, he revealed the deepest secrets of the Kabbalah. Lag BaOmer therefore became a day of celebration of the great light (i.e., wisdom) that Bar Yochai brought into the world.

Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson, writes in his Likkutei Sichos that a deeper reason for the term Lag BaOmer is that the Hebrew words Lag BaOmer (ל״ג בעמר, spelled without the “vav”), have the same “gematria” – numerical count, as Moshe (משה, Moses). He writes that Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai, whose anniversary of death is traditionally observed on this day, was mystically a spark of the soul of Moses. It is customary at the Meron celebrations, dating from the time of Rabbi Isaac Luria, that three-year-old boys be given their first haircuts (upsherin), while their parents distribute wine and sweets. Similar upsherin celebrations are simultaneously held in Jerusalem at the grave of Shimon Hatzaddik for Jerusalemites who cannot travel to Meron. This explains the multitude of families with little children traveling on the train to Meron.

Mass pilgrimages to tombs of holy sages, martyrs, or healers, are known in all religions. In some it is proscribed as part of religious practice, and in others it is established by popular movements and mystic beliefs. The pilgrimage on Lag BaOmer to Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai’s grave has another explanation which stems from a Talmudic passage. It states that during the time of Rabbi Akiva, 24,000 of his students died from a divinely-sent plague during the counting of the Omer. The Talmud goes on to say that this was because they did not show proper respect to one another.

According to a tradition of the Talmudic rabbis, the plague ended on Lag Ba Omer. For this reason, the period of mourning which coincides with the counting of the Omer is suspended on Lag BaOmer. According to Jewish religious tradition, after the death of Rabbi Akiva’s 24,000 students, he was left with only five students, among them Rabbi Shimon Bar Yochai. The latter went on to become the greatest teacher of Torah in his generation, and is purported to have authored the Zohar, a landmark text of Jewish mysticism. The actual authorship of the Zohar has been disputed, and scholarship generally points to Moses de León as the author of the Zohar, pseudo-epigraphically attributed to Bar Yochai by him in an attempt to legitimize the work.

The Zohar calls the day of Bar Yochai’s death a hillula – celebration. Rabbi Chaim Vital, the main disciple of Rabbi Isaac Luria and author of Etz Chaim, was the first to name Lag BaOmer as the date of Bar Yochai’s hillula. According to the Zohar (III, 287b–296b), on the day of Bar Yochai’s death, he revealed the deepest secrets of the Kabbalah. Lag BaOmer therefore became a day of celebration of the great light (i.e., wisdom) that Bar Yochai brought into the world.

Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson, writes in his Likkutei Sichos that a deeper reason for the term Lag BaOmer is that the Hebrew words Lag BaOmer (ל״ג בעמר, spelled without the “vav”), have the same “gematria” – numerical count, as Moshe (משה, Moses). He writes that Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai, whose anniversary of death is traditionally observed on this day, was mystically a spark of the soul of Moses. It is customary at the Meron celebrations, dating from the time of Rabbi Isaac Luria, that three-year-old boys be given their first haircuts (upsherin), while their parents distribute wine and sweets. Similar upsherin celebrations are simultaneously held in Jerusalem at the grave of Shimon Hatzaddik for Jerusalemites who cannot travel to Meron. This explains the multitude of families with little children traveling on the train to Meron.

The best-known custom of Lag BaOmer is the lighting of bonfires throughout Israel and worldwide wherever religious Jews can be found. In Meron, the burial place of Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai and his son, Rabbi Eleazar, hundreds of thousands of Jews gather throughout the night and day to celebrate with bonfires, torches, song and feasting. This was a specific request by Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai of his students. Some say that as Bar Yochai gave spiritual light to the world with the revelation of the Zohar, bonfires are lit to symbolize the impact of his teachings. As his passing left behind such a “light”, many candles and/or bonfires are lit. Another reason for the lighting of bonfires is brought by the book Bnei Issachar. On the day of his death, Rabbi Shimon Bar Yochai said, “Now it is my desire to reveal secrets… The day will not go to its place like any other, for this entire day stands within my domain…” Daylight was miraculously extended until Rabbi Shimon completed his final teaching and died. This symbolized that all light is subservient to spiritual light, and particularly to the primeval light contained within the mystical teachings of the Torah. As such, the custom of lighting fires symbolizes this revelation of powerful light. Historically, children across Israel and abroad used to go out and play with bows and arrows, reflecting the Midrashic statement that the rainbow (the sign of God’s promise to never again destroy the earth with a flood; Genesis 9:11–13) was not seen during Bar Yochai’s lifetime, as his merit protected the world.

The best-known custom of Lag BaOmer is the lighting of bonfires throughout Israel and worldwide wherever religious Jews can be found. In Meron, the burial place of Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai and his son, Rabbi Eleazar, hundreds of thousands of Jews gather throughout the night and day to celebrate with bonfires, torches, song and feasting. This was a specific request by Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai of his students. Some say that as Bar Yochai gave spiritual light to the world with the revelation of the Zohar, bonfires are lit to symbolize the impact of his teachings. As his passing left behind such a “light”, many candles and/or bonfires are lit. Another reason for the lighting of bonfires is brought by the book Bnei Issachar. On the day of his death, Rabbi Shimon Bar Yochai said, “Now it is my desire to reveal secrets… The day will not go to its place like any other, for this entire day stands within my domain…” Daylight was miraculously extended until Rabbi Shimon completed his final teaching and died. This symbolized that all light is subservient to spiritual light, and particularly to the primeval light contained within the mystical teachings of the Torah. As such, the custom of lighting fires symbolizes this revelation of powerful light. Historically, children across Israel and abroad used to go out and play with bows and arrows, reflecting the Midrashic statement that the rainbow (the sign of God’s promise to never again destroy the earth with a flood; Genesis 9:11–13) was not seen during Bar Yochai’s lifetime, as his merit protected the world.

In modern Israel, early Zionists redefined Lag BaOmer from a rabbinic-oriented celebration to a commemoration of the Bar Kokhba revolt against the Roman Empire. For Zionists, the bonfires are said to represent the signal fires that the Bar Kokhba rebels lit on the mountaintops to relay messages. The Romans forbade the kindling of fires that were used to signal the start of each Jewish month and thus determine the dates of holidays. This interpretation of the holiday reinforced the Zionist reading of Jewish history and underscored their efforts to establish an independent Jewish state. As Rabbi Benjamin Lau writes in Haaretz:

In modern Israel, early Zionists redefined Lag BaOmer from a rabbinic-oriented celebration to a commemoration of the Bar Kokhba revolt against the Roman Empire. For Zionists, the bonfires are said to represent the signal fires that the Bar Kokhba rebels lit on the mountaintops to relay messages. The Romans forbade the kindling of fires that were used to signal the start of each Jewish month and thus determine the dates of holidays. This interpretation of the holiday reinforced the Zionist reading of Jewish history and underscored their efforts to establish an independent Jewish state. As Rabbi Benjamin Lau writes in Haaretz:

Beyond our back yard there is a footpath above the wadi and nature reserve. Every year except last year during the pandemic we witnessed young children gathering planks of wood and any kind of flammable material for creating bonfires. We even gathered with a bunch of neighbors and their children around a lovely bonfire at the abandoned lot beside our houses and baked potatoes wrapped in aluminum foil in the fire.

Beyond our back yard there is a footpath above the wadi and nature reserve. Every year except last year during the pandemic we witnessed young children gathering planks of wood and any kind of flammable material for creating bonfires. We even gathered with a bunch of neighbors and their children around a lovely bonfire at the abandoned lot beside our houses and baked potatoes wrapped in aluminum foil in the fire.  We sang songs, ate watermelon, and when we finished, we made sure the fire was doused with sand and water so it would not spread. Indeed, one year we found a fire burning on the footpath below our back yard, and called the firefighters. When he saw the embers still smoldering in the morning, my husband took things into his own hands and put out the fire with a pail of water. I’d really rather have these kinds of memories than the horrible sights from the trampling of masses.

We sang songs, ate watermelon, and when we finished, we made sure the fire was doused with sand and water so it would not spread. Indeed, one year we found a fire burning on the footpath below our back yard, and called the firefighters. When he saw the embers still smoldering in the morning, my husband took things into his own hands and put out the fire with a pail of water. I’d really rather have these kinds of memories than the horrible sights from the trampling of masses. I know that for the past 12 years there have been negotiations with the Safed Sefardi Religious Authority to transfer responsibility for the tomb (including securing Lag BaOmer events) to the Israeli legal authorities. In that case, perhaps the number of worshipers will indeed be limited to the safe capacity of the space. I am certainly for freedom of practice and respect of each other, but within the bounds of safety. Last year’s pandemic showed that the government caves in to political pressures, even on questions of life and death. Unfortunately this event clearly demonstrated the results of such conduct.

I know that for the past 12 years there have been negotiations with the Safed Sefardi Religious Authority to transfer responsibility for the tomb (including securing Lag BaOmer events) to the Israeli legal authorities. In that case, perhaps the number of worshipers will indeed be limited to the safe capacity of the space. I am certainly for freedom of practice and respect of each other, but within the bounds of safety. Last year’s pandemic showed that the government caves in to political pressures, even on questions of life and death. Unfortunately this event clearly demonstrated the results of such conduct.